US grand strategy and Saudi counterterrorism: turning domestic insurgents into mercenaries

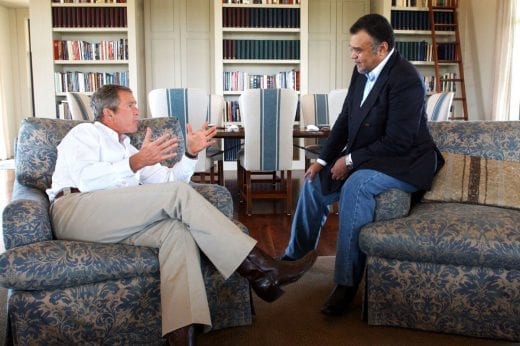

Prior to his ouster in a palace coup Crown Prince Mohammed bin Nayef was viewed by US and British intel agencies as someone they could very much do business with. Indeed, he had been educated in the US and later received training from the FBI and Scotland Yard.

Mohammed bin Nayef (MBN) had been for over a decade the Saudi regime’s most influential security official. Former director George Tenet regarded MBN as the CIA’s closest partner in fighting Al Qaeda, and the threat it posed to the House of Saud during 2003-6. The Prince “was someone in whom we developed a great deal of trust and respect,” Tenet said.

MBN would become head of Saudi intelligence in February 2012. Under his adviser and intel chief Saad Aljabri, MBN’s security ministries ran a network of informants inside Al-Qaeda in the Kingdom. The CIA would award MBN a medal in 2017. He had received the Legion d’honneur from the French also.

Lauded as the most successful Arab intelligence officer, he had access to President Obama’s inner circle. His approach to ‘counterterrorism’ in the desert kingdom was praised as “savvy” and “accomplished”.

Heading up the Ministry of the Interior, he was sometimes criticised in hand-wringing articles from US thinktanks and liberal media for treating human rights activists as ‘terrorists’. But it was approach to extreme Sunni militancy that interests me here.

That Al Qaeda was first formed by Saudi salafists and received much of its funding from powerful families in the country was an open secret, especially after the 9-11 attacks. This was a tricky issue for both the House of Saud and its sponsors in Washington and London.

A report reluctantly commissioned by Theresa May’s Home Office in January 2016 on funding for Islamist terrorism was subsequently left unpublished.

The shelving came to light in the aftermath of the Manchester Arena bombing, in May 2017. As a spokesman for the Liberal Democrats wrote:

It is no secret that Saudi Arabia in particular provides funding to hundreds of mosques in the UK, espousing a very hardline Wahhabist interpretation of Islam. It is often in these institutions that British extremism takes root.

The report’s contents were considered too sensitive to publish, given the UK’s close cooperation with the Saudi regime. Prime Minister May had previously defended the extensive relationship as being effective counterterrorism, “keeping the streets of Britain safe“.

A decade or so earlier MBN’s innovations in ‘counterterrorism’ centred around the ‘rehabilitation’ of militants. Special prisons were built, including the ‘Mohammed bin Nayed Centre for Counselling and Care’. Dubbed in the media as ‘Betty Ford for jihadists’ (mostly captured Al-Qaeda operatives).

Described as ‘cushy’ the approach would involve perks for its ‘beneficiaries’, including gyms, and passes out to attend weddings and funerals. Families of the inmates would be involved in their ‘care’ and would receive allowances for housing, medical treatment and education. And so would have a stake in the successful ‘rehabilitation’ of the wayward men.

But it appears this level of indulgence and largess was not extended to human rights activists. A critique of the policy found that:

The programmes’s counsellors reportedly seek less to disabuse imprisoned militants of their hard-line views than to reinforce the primacy of the Saudi state in determining the appropriate use of violence.

While non-violent rights activists were usually banned from travel overseas, ‘graduates’ of the centre could have international travel facilitated for them. As a father of a graduate said: “If you’re in Al Qaeda, they reason with you, give you money, a car, a wife.”

There was, reportedly, a high rate of recidivism with many militants arrested after Al Qaeda attacks, turning out to be have been graduates of the special prisons. It also appears that jihadists returning from Afghanistan, Syria and elsewhere would often be sent for a stay at the special centres.

The House of Saud had gambled that they would not be overthrown by Al Qaeda, as long as they continued to tolerate Wahhabi schools and found a modus viviendi with domestic militants.

This ‘innovative’ approach to managing the Kingdom’s problem with Al Qaeda seems to have developed in the same period as a shift in American policy on the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. It is in this context that MBNs counterterrorist programmes must be understood.

This shift in US strategy took place in the years following the invasion of Iraq. It was reported on by Seymour Hersh in a February 2007 article for the New Yorker entitled ‘The Redirection’. Given all that has passed since, it can in my view, be considered a landmark piece of reportage.

According to Hersh’s reporting, US policy making circles were dismayed to see that the invasion of Iraq had led to an upsurge of Iranian influence in the region. Although they had recently focused their post 9-11 efforts on targeting Sunni militancy, a strong anti-Iranian sentiment among the US policy elite would mean a ‘redirection’, towards weakening Iran and its perceived allies in the region – chiefly Syria and Hezbollah.

Citizens in the US, Britain and elsewhere had protested en masse against the invasion of Iraq. So there clearly wasn’t public appetite for further large-scale military operations in the region. A different approach would have to be employed in order to realise the objectives.

The Machiavellian plan would see US agencies, and their British sidekicks, forge an alliance between the House of Saud, salafist militancy, Qatar, Turkey and themselves, with the approval of Israel.

The danger of working with the Salafis was self-evident. Sources that spoke to Hersh acknowledged they would be, “mobilising the worst kind of Islamic radicals. Once you get them out of the box, you can’t put them back.” And that the Salafis were “sick and hateful…if you try to outsmart them, they will outsmart us. It will be ugly.”

But US policy makers considered weakening Shi’ite influence in the region and smashing the remnants of Arab Nationalism as their primary objectives. The political outlook of the Salafist Muslim Brotherhood had long been understood as being more amenable to the economic and corporate imperatives of the anglo-american deep state.

A fellow at the Council of Foreign Relations Hersh spoke to:

..compared the current situation to the period in which Al Qaeda first emerged. In the nineteen-eighties and the early nineties, the Saudi government offered to subsidize the covert American C.I.A. proxy war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. Hundreds of young Saudis were sent into the border areas of Pakistan, where they set up religious schools, training bases, and recruiting facilities. Then, as now, many of the operatives who were paid with Saudi money were Salafis. Among them, of course, were Osama bin Laden and his associates, who founded Al Qaeda, in 1988.

This time, the U.S. government consultant told me, Bandar and other Saudis have assured the White House that “they will keep a very close eye on the religious fundamentalists. Their message to us was ‘We’ve created this movement, and we can control it.’ It’s not that we don’t want the Salafis to throw bombs; it’s who they throw them at—Hezbollah, Moqtada al-Sadr, Iran, and at the Syrians, if they continue to work with Hezbollah and Iran.”

As the programme was to be largely funded by the Saudis and Qataris, Congressional and Parliamentary oversight could be bypassed by the three letter agencies involved. It could be done ‘off the books’, in a similar fashion to the Iran-Contra funding scheme for operations against Nicaragua’s Sandinistas in the 1980s.

Hersh’s article is evidence that the quote unquote ‘Syrian Revolution’ was not so much a groundswell from the streets after the Arab Spring, but something having its roots, more perhaps, in Fort Meade, Maryland and Vauxhall Cross, London. Sy Hersh’s reporting implies that US clandestine activities in support of the Muslim Brotherhood against the Baathist state were already underway by late 2006. This is over four years before the Arab Spring and the supposed ‘Syrian revolution’.

American General Wesley Clark said publicly in 2007, that shortly after 9-11 Pentagon officials told him the plan was to: “take out 7 countries in 5 years: Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Iran.“

I’m sceptical about the motives and timing of his ‘disclosure’. Others have sensed faux naivete in the interview. But it seems the public were being prepared to accept further chaos in MENA, and to have the impression that this was consistent with prior strategizing.

In 2013, former French foreign minister Roland Dumas would let slip on a talk show, that in 2009 he had met with officials at the British foreign office who were planning to oust the government of Syria.

While the BBC had been active in Syria (pdf) since at least 2004 working to make it a more conducive place for liberal ‘civil society’ and western ‘development’ NGOs.

It appears to be the case that MBN’s success in taking on domestic Al Qaeda militancy in the mid-2000s was to serve as a basis to enable the ‘redirection’ of jihadis; from domestic insurgency into effective mercenaries for regime change in Libya and Syria, and as a counterweight to the growing Ansarallah (Houthi) movement in Yemen.

Viewed in this context the rationale for elements of MBNs unusual ‘counterterrorism’ spending can be discerned. Ostensibly, the spending was undertaken with the aim to “recruit personnel and develop intelligence service contacts to penetrate Al-Qaeda.” But a few more details about the secret programmes have since come to light in relation to the case of Saad Aljabri.

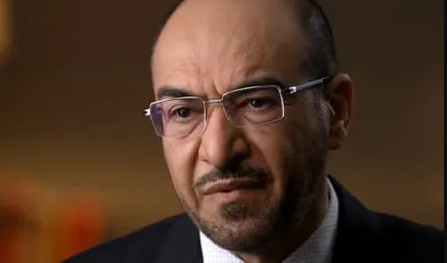

Aljabri was MBN’s right-hand man at the Ministry of Interior, a most senior non-royal security official, regarded by US officials as a ‘deep state liason’ between the Kingdom and the ‘five-eyes’ powers.

He is, though, now holed up in Canada after slipping out of the Kingdom to Turkey in May 2017, not long before his patron’s ouster and house arrest.

Security agencies there acknowledge that he is a likely target for Mohamed bin Salman’s hit squads. He seems to be a man who knows rather too much, as this account of the Palace coup relates: “He knows every foible, every misstep that Saudi royals have made.“

“In my opinion, he holds the keys to Pandora’s box for the current Crown Prince” said a former Canadian intel officer. “Any secrets they have, business dealings, security issues — it is information I’m sure the current Crown Prince wouldn’t want in public.”

Aljabri, accused of embezzlement, is the subject of lawsuits by state linked firms in Saudi. But the firms were first set up through MBN’s personal counterterrorism account. A network of front companies was established as “vehicles in the private sector to disguise sensitive activities.“

Aljabri and MBN’s defenders point to a December 2007 decree from King Abdullah authorising the spending. They say they were following ‘standard practice’ for intelligence agencies. A practice they had presumably picked up from their tutors in the western security apparatus. The 2007 decree authorised outlays for:

- Secret airports

- Aviation transport services

- Contracts with a Turkish construction company

- Security resources (including weapons and encrypted communications)

Somewhat surprising items for a domestic counterterrorism budget. The proportion of Interior Ministry revenues flowing into MBN’s own counterterrorism account would be boosted in subsequent years.

US and Canadian officials would prefer that the lawsuits against Aljabri be settled out of court to avoid disclosure of any sensitive details about covert US-Saudi programmes. In Boston, one of the cases has been thrown out of court. The director of US National Intelligence, Avril Haines invoked state secrets privilege to prevent disclosure of classified information damaging to ‘national security’. Similar motions have been filed by the Canadian CSIS in Ontario courts.

It seems that the door for MBN’s ouster in June 2017 was opened as the progress of the proxy military operations against the Syrian Arab Republic ground to a halt. And the consequences of adopting a ‘counterterrorism’ approach that enabled Al Qaeda linked sick salafis got out of hand, not least for the British; who had adopted their own soft approach to homegrown jihadis. I’ll take a closer look in a subsequent article.

Interested readers can find many sources on the connections of Manchester Arena suicide bomber on the page on A Closer Look on Syria